Many folks in the Lake Pepin area have enjoyed a sunset meal at Ted Fischer and Robbie Bannen’s farm. Their A-to-Z Produce & Bakery in Maiden Rock, Wisconsin, hosts a bi-monthly wood-fired pizza night that has attracted thousands of folks over the years to try their handmade pizzas crafted from ingredients grown and raised on-site. They even mill their own wheat! As a no-spray, regenerative farm for decades, Ted and Robbie test their well water annually.

Ted reports that the nitrate levels in their water have rarely ever been below 10 ppm - the EPA-recommended safe level.

"Water testing just needs to be easy and free for everyone. Right now, the states count on neighbors to report each other applying nitrogen at the wrong time, that's not realistic. There has to be enforcement at the local level."

Even the need to test their water illustrates a painful and growingly more common irony for many producers who, despite their best farming efforts, are forced to buy, filter, or even shoulder the expense of drilling new wells to drink clean water.

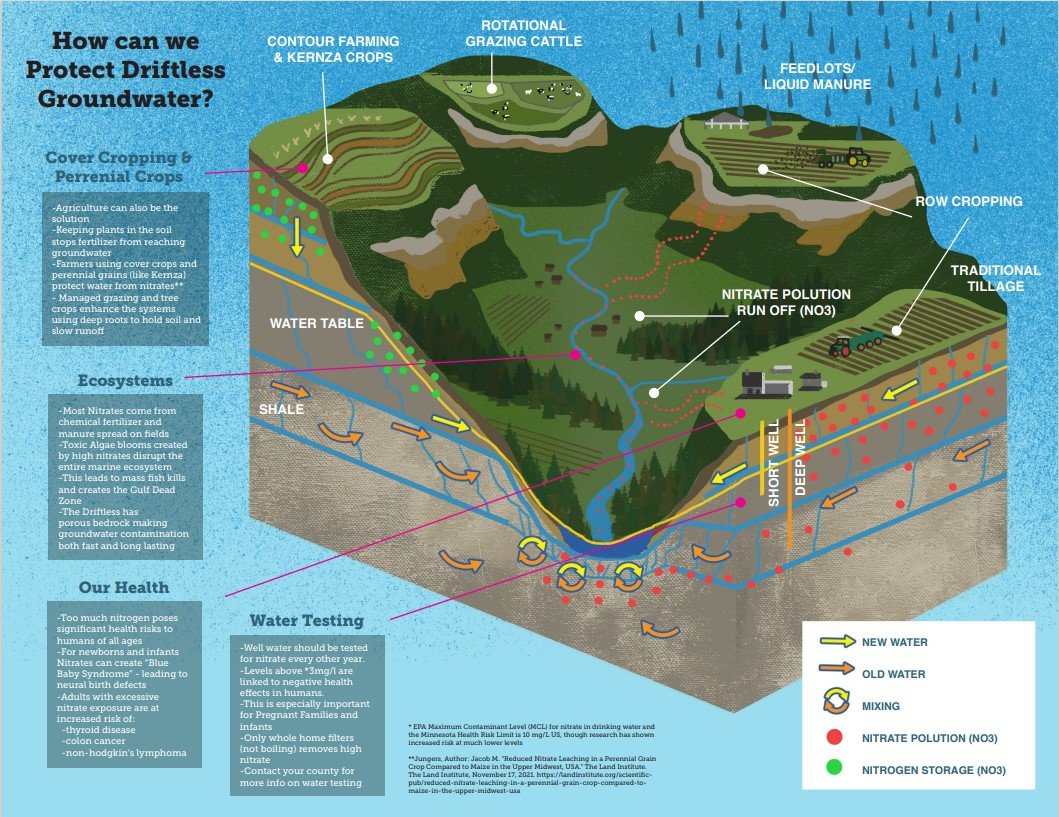

NITROGEN VS. NITRATES

Nitrogen is a naturally occurring element critical to human and plant life, it is a core component of the fertilizers and manure spread in mass quantities on farms in the Midwest. When the nitrogen mixes with oxygenated water, it forms nitrate. Drinking water with high levels of nitrate can cause methemoglobinemia, or “blue baby syndrome,” a potentially life-threatening condition affecting the blood’s ability to carry oxygen throughout the body. Nitrates also have been linked to thyroid disease and certain cancers. Nitrate pollution is largely caused by agricultural runoff. Rainwater picks up the nitrogen in fertilizer and manure and carries it to bodies of water. When nitrate reaches the underground drinking water supply, it’s the good owners’ responsibility to treat their water — with limited, often expensive options — or find another water source.

In Minnesota, nitrate pollution disproportionately impacts low-income communities, according to a 2021 study by the Environmental Working Group. The study found that in Minnesota, 73% of water utilities with elevated nitrate were in areas that fell below the average state income. In Wisconsin, the story is the same. Tia Johnson, Wisconsin NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice chair, reports,

“NAACP’s Wisconsin chapter has reviewed data regarding nitrate drinking water contamination in the state. Nitrate contamination is harming drinking water in several communities with significant numbers of people of color and people living below the poverty line. It is unjust to continue shifting human health and environmental costs of unsustainable farming practices onto vulnerable communities that are least able to protect themselves.”

Well water in Pierce County is particularly vulnerable to impairments due to the porous bedrock that sits between fields and well water sources. Rainwater picks up nitrogen in fertilizer and manure and carries it to nearby bodies of water (i.e., Rush River) or it seeps into the ground. In the 2022 Wisconsin Groundwater Coordinating Council Report to the Legislature (GCCFullReport2022.pdf (wisconsin.gov)), it was estimated that nearly 15% of private wells (689 wells) in Pierce County were over the health standard of 10 ppm. Research has shown increased risk at lower levels and the EPA has found concentrations greater than 3 mg/L indicate contamination from human activity (Report Finds Wisconsin Is Among 10 States Where Nitrate Contamination Is Getting Worse | Wisconsin Public Radio (wpr.org)). In nearby Pepin County, 20% of wells (320) were above the health limit.

While small farmers bear the brunt of fertilizer and input costs increase to maintain pace with their past production, small towns are left to carry the bill for treating citizens’ water. A 2018 study by Schechinger and her EWG colleague Craig Cox found that in small communities, the potential cost of building and operating a nitrate treatment plant ranged from $47 to $378 per person per year. A 2015 report by the Minnesota Environmental Quality Board found that in the most extreme cases, obtaining the needed nitrate treatments would cost thousands of dollars per household.

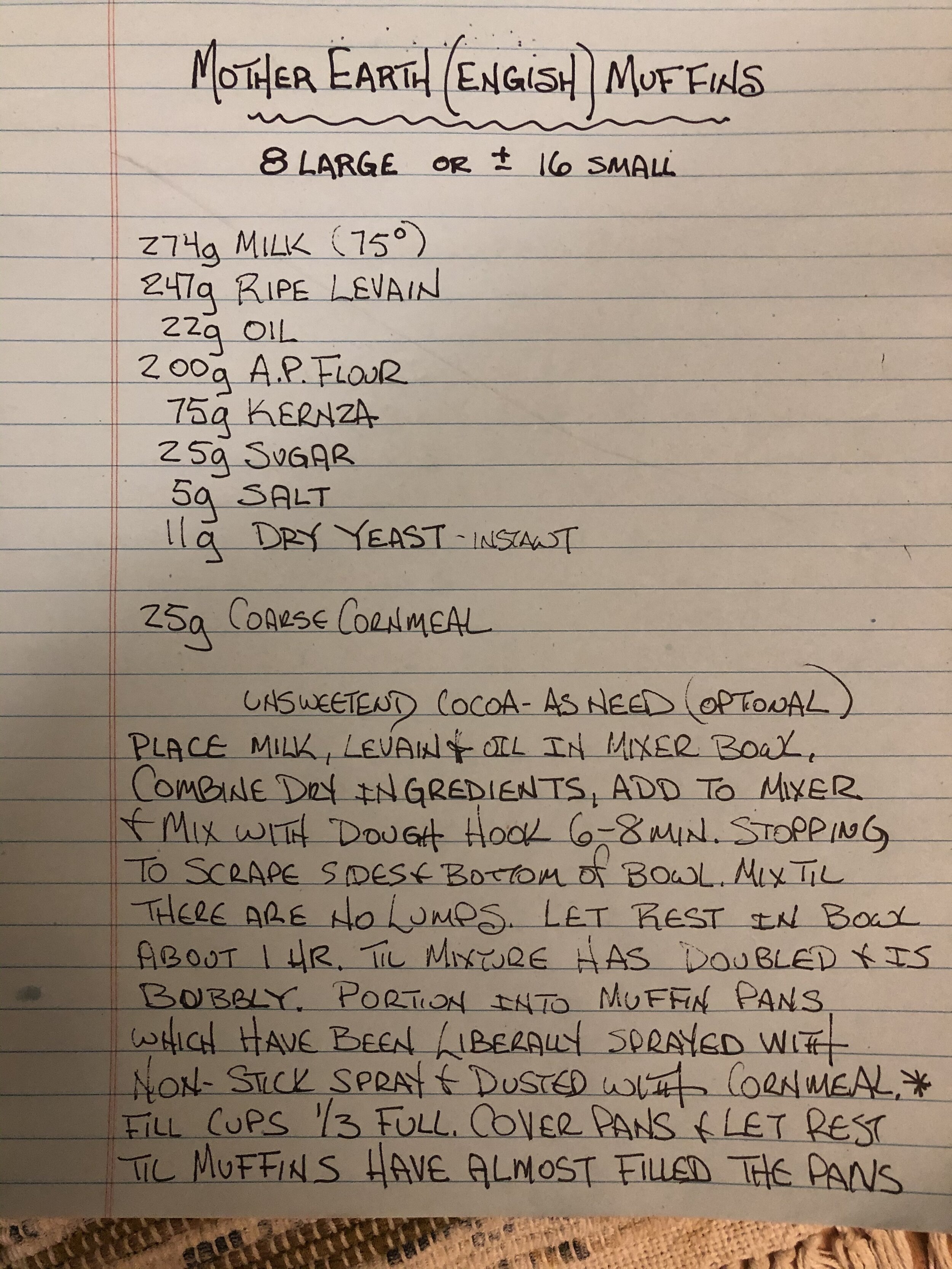

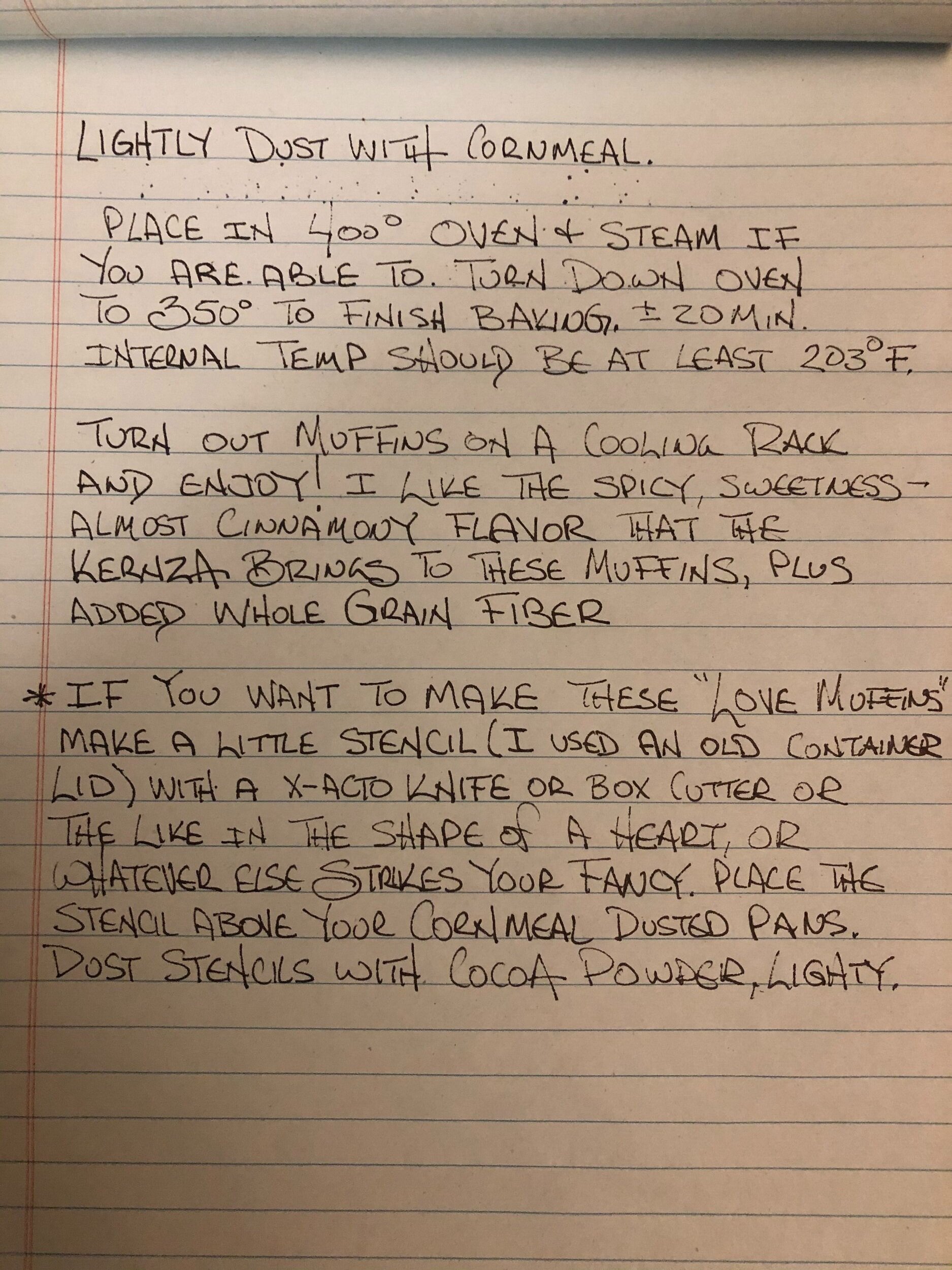

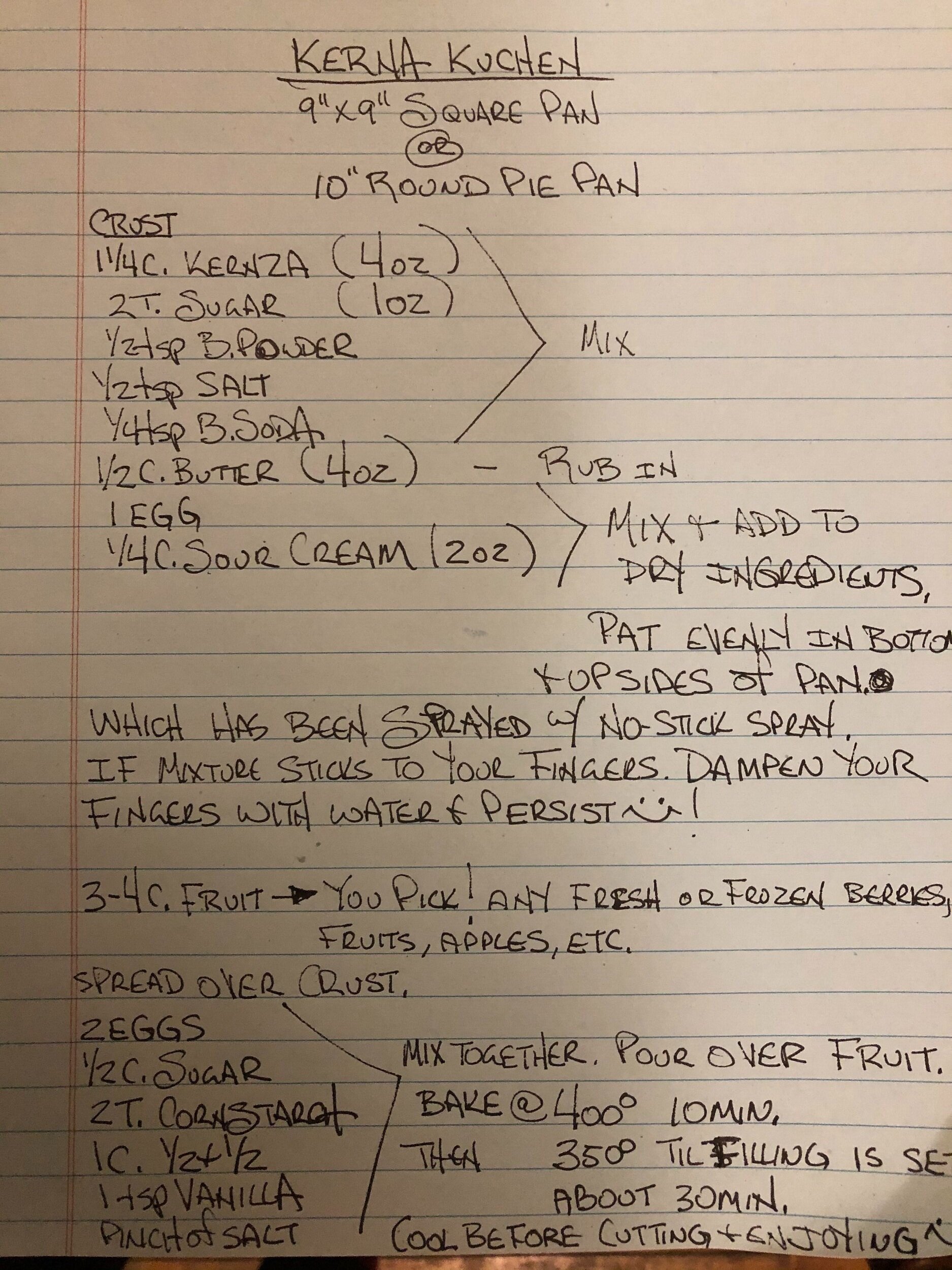

Preventing nitrate from entering drinking water sources is more effective and less expensive than removing nitrate from the water. Conservation practices that reduce nitrate contamination can include setting aside land that borders a well, planting cover crops on fields in between corn and soy rotations, more widespread adoption of perennial crops, and using a fertilizer that releases nitrogen slowly. Funds from the federal Infrastructure Bill (IRA) are specifically targeted at programs that decrease water pollution up and down the Mississippi and its watersheds. The upcoming Farm Bill offers an exciting opportunity to fund and incentivize more careful stewardship of our water and soils - particularly in sensitive areas.

I reached out to Ted and Robbie's son Emet Fischer and his wife Cella Langer who operate a vegetable dairy and vegetable operation in Hager City, Wisconsin, called Oxheart Farm.

Cella said that right before they signed on their loan they had to submit clean well water results to access their financing.

Cella said it was shocking to realize that their dream farm could be lost due to polluted water from past generations.

How can we expect emerging farmers with the skills and education to steward our local land and water resources to shoulder the burden of past management? For the first time and likely just in time, we can create informed, realistic enforcement and safeguard our nation's precious fresh water. This Farm Bill can take the largest public infrastructure bill in history and create holistic protections.

Blog post written by Alex Keilty, LPLA Program Director